“ Trick shots are like happiness because they are my moments, it’s mine”

— Gael Monfils.

From Bill Tilden and Jimmy Connors to Roger Federer and now Carlos Alcaraz, tennis champions have captivated crowds with their trick shots, creative mimes, and amusing wisecracks. These geniuses abounded in talent, flair, and audacity, and they often flaunted it. These charismatic characters brought drama, controversy, and beauty. The cultural historian Elizabeth Wilson noted in her illuminating book, Love Game, that while tennis was similar to art, it had a significant difference.

“Like the medieval jousting tournament or the Spanish bullfight, the tennis spectacle was simultaneously art and contest,” wrote Wilson. “So, whereas when Nureyev danced, he had a free field on which to display his virtuosity and the beauty of his art, the tennis player was condemned to force his brilliance against an opponent. It is from this that tennis (more, I would argue, than other individual sports and certainly more than team sports) derives its tension: the unremitting pull between the art and the fight.”

Epitomising both elements, Tilden, a larger-than-life 1920s superstar, was renowned for intentionally falling behind inferior opponents in early-round matches. As cries of “Tilden’s in trouble!” spread, spectators scurried to see him pull off another theatrical comeback.

In another party trick, the imperious American held five balls in his massive hand, fired four straight aces to win a game, and then casually tossed the fifth ball into the stands. “Tilden always seems to have a thousand means of putting the ball away from his opponent’s reach. He seems to exercise a strange fascination over his opponent as well as the spectators,” wrote archrival Rene Lacoste in his 1928 book, Lacoste on Tennis.

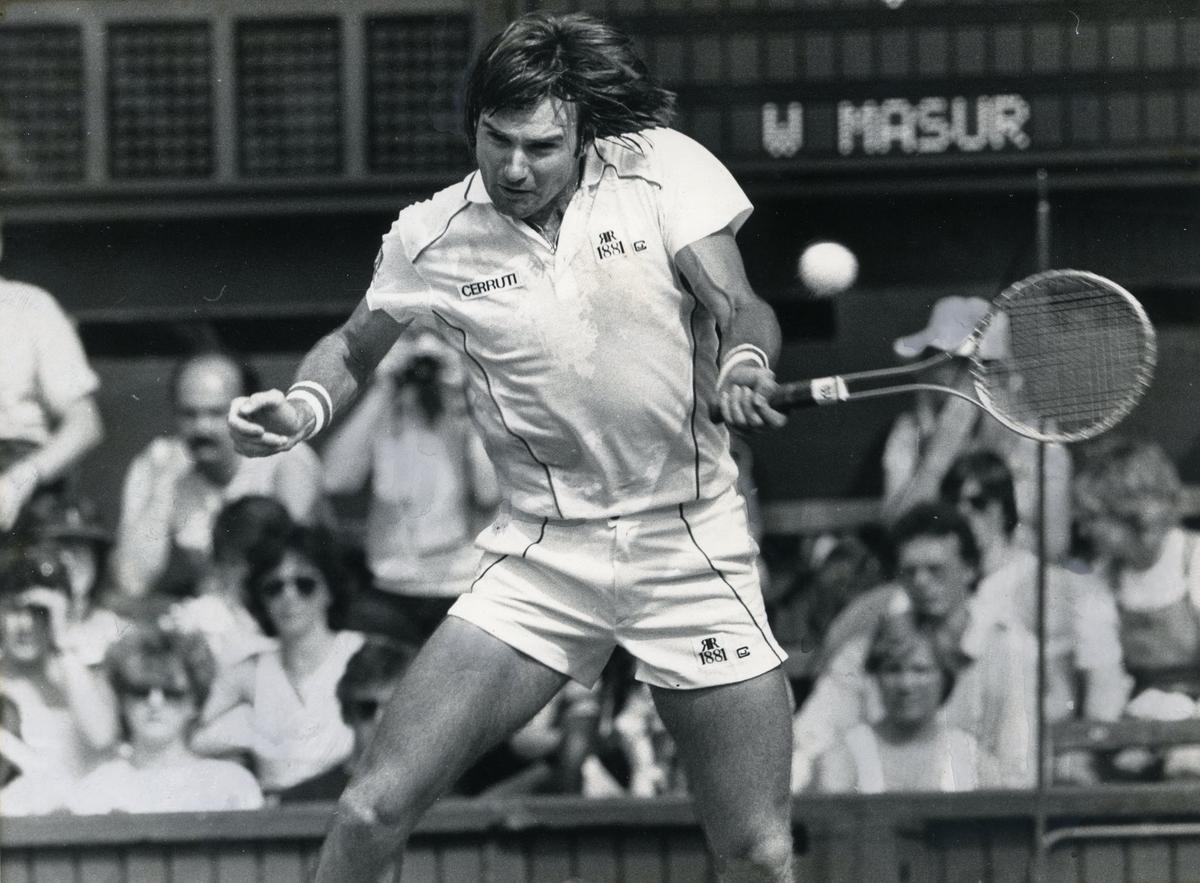

Mercurial genius: The pugnacious Jimmy Connors elicited powerful emotions.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu

Mercurial genius: The pugnacious Jimmy Connors elicited powerful emotions.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu

Tilden’s passion to perform and his love of the dramatic arts made him a natural for Hollywood’s fast-growing silent film industry. The sports hero drew mixed reviews as an actor. After playing a ‘pseudo tramp’ in the Broadway comedy, They All Want Something, the New York Times reviewer wrote that it was “at best only moderately entertaining” and had “none of the vitality he shows on the tennis courts.” But the New York Journal review said that the budding thespian “moved with all the grace and stage presence of a seasoned actor.” Bill also became a playwright and producer, sometimes investing in his creations.

Much like Tilden, the pugnacious Connors elicited powerful emotions. Reviled in the 1970s for being rude, crude, and lewd — even mimicking masturbation — on the court, Jimbo was revered in the 1980s. Fist pumping — which he claimed he invented in tennis, animalistic grunts, powerful two-handed backhands, the Jimmy Cagney strut, and repartee with spectators make this rebel without a pause can’t-miss TV for the sporting masses.

Connors’s rivalries with the stoical Bjorn Borg, irascible John McEnroe, and dour Ivan Lendl provided riveting, high-stake matches, as did his 1975 Wimbledon final against Arthur Ashe. But his fiery competitiveness was never more appreciated than at age 39 during his comeback victory — he trailed 5-2 in the fifth set — over Aaron Krickstein, 15 years his junior, in the 1991 US Open quarterfinals. After belting a winner, the ageless warrior yelled toward a court microphone, “This is what they came for! This is what they want!”

On five-time winner Connors’s love affair with the boisterous US Open fans, Chris Evert, his former fiancée, told USTA Magazine, “No one ever made a tennis court come alive more.”

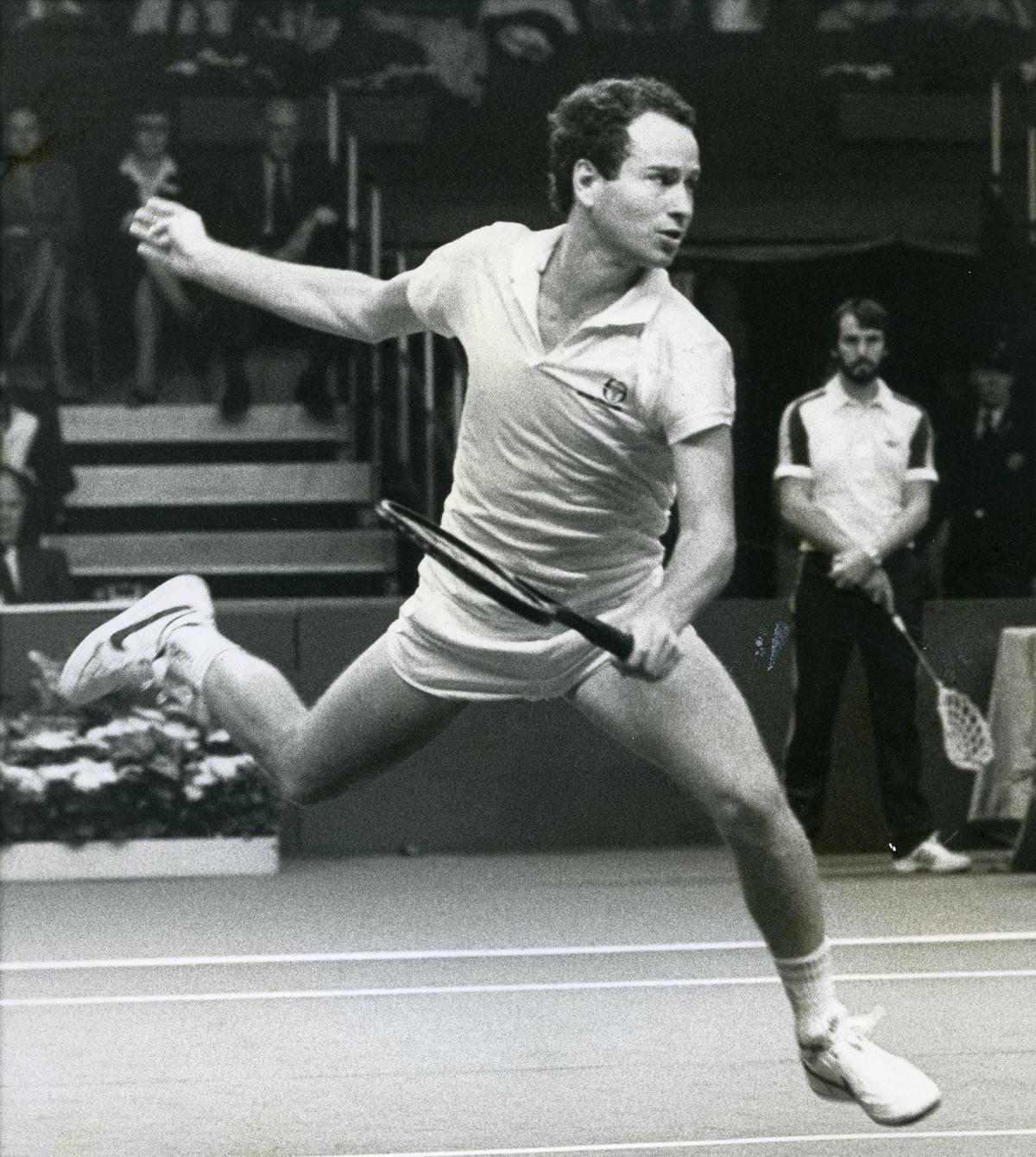

Though John McEnroe’s outbursts outraged many, even his severest critics admired his shot-making genius, especially his exquisite volleys.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu

Though John McEnroe’s outbursts outraged many, even his severest critics admired his shot-making genius, especially his exquisite volleys.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu

An artist with a racquet

John McEnroe, another fiery, Irish American lefty, said the compliment he relished most during his halcyon days was being called an artist. Though his outbursts outraged many, even his severest critics admired his shot-making genius, especially his exquisite volleys. “In terms of tennis talent, I’ve never seen anyone better than John,” Ashe once said.

McEnroe captured four US Open and three Wimbledon titles, but he undoubtedly could have won more majors. He was fuelled by a rage for perfection, a Vesuvian rage that could explode at any time and often targeted lines people and umpires. “I want to change. I gotta change. I don’t want to be some maniac,” he confided in 1981.

Clay was McEnroe’s least effective surface, and the French Open failures left a glaring gap in his resume. In 1984, after he outclassed Connors 7-5, 6-1, 6-2 in the semifinals, he again looked unstoppable against 24-year-old Lendl in the first two sets, allowing only 10 points in his nine service games. McEnroe tormented and bewildered his mechanical foe with vicious lefty serves, stinging volleys, feathery drop shots, and clever angles. The artist was painting a masterpiece on the terre battue in Paris.

Ahead 6-3, 6-2, 1-1, the high-strung New Yorker angrily grabbed a TV cameraman’s headset that was emitting loud noise, yelled “Shut up!” and threw it aside. Most of the already pro-Lendl crowd of 18,000 started booing and whistling. McEnroe lost his poise, the momentum, and eventually the final 3-6, 2-6, 6-4, 7-5, 7-5.

“It was the worst loss of my life, a devastating defeat: Sometimes it still keeps me up at nights,” McEnroe confided in his 2002 autobiography, You Cannot Be Serious. “It’s even tough for me now to do the commentary at the French — I’ll often have one or two days when I literally feel sick to my stomach just at being there and thinking about that match. Thinking of what I threw away, and how different my life would’ve been if I’d won.”

Ever since the first Wimbledon staged in 1877, talented showmen have had to navigate the tension Elizabeth Wilson described in a sport where split-second decisions can make the difference between victory and defeat. It’s a truism that sports — especially tennis — reveal character as much as build character.

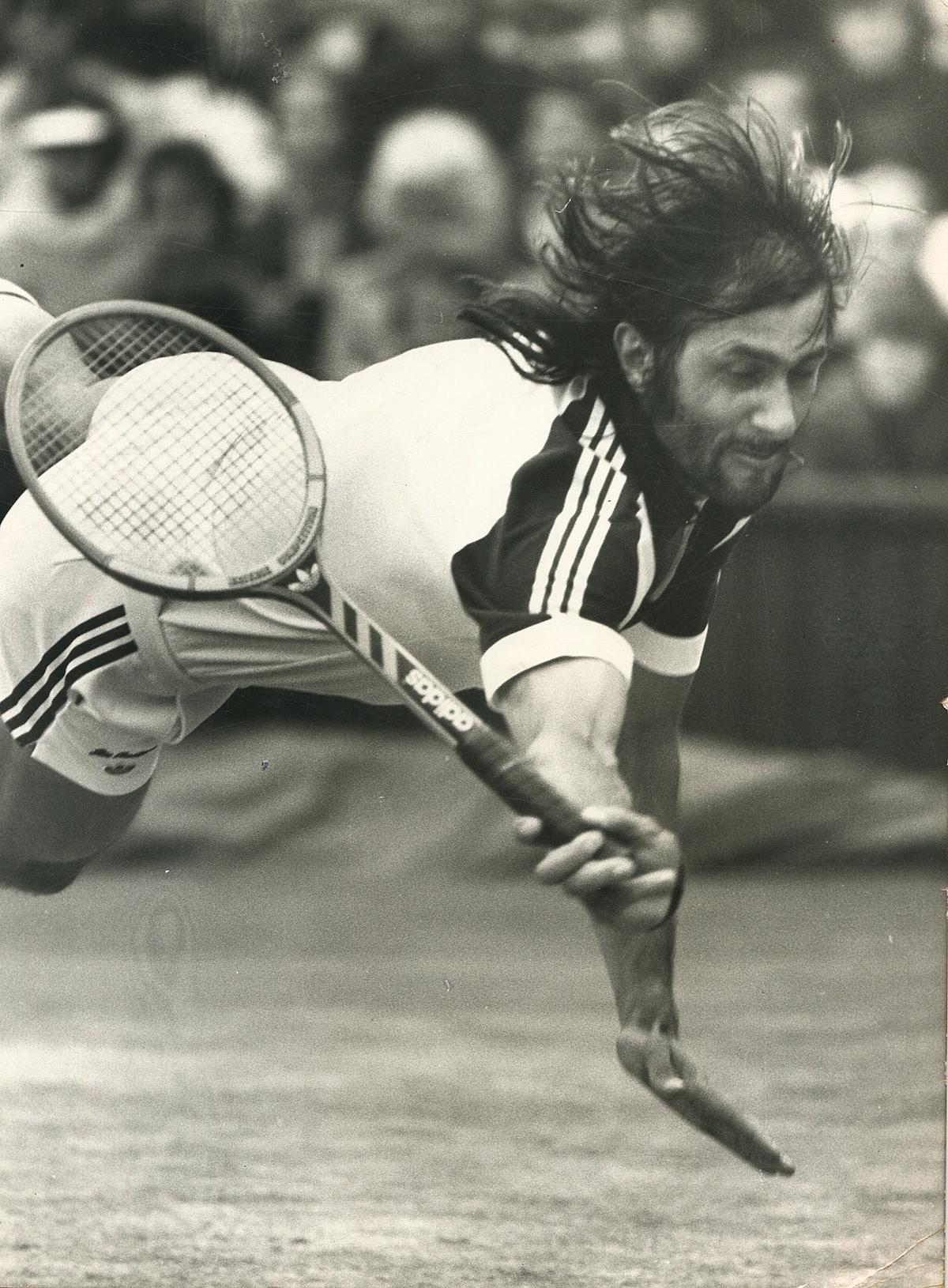

Not since frankie Kovacs had big-time tennis witnessed anything like the buffoonery of Ilie Nastase in the 1970s.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu

Not since frankie Kovacs had big-time tennis witnessed anything like the buffoonery of Ilie Nastase in the 1970s.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu

The mostly forgotten Frankie Kovacs attests to that. Nicknamed the ‘Clown Prince of Tennis,’ the handsome 6’4” Kovacs became notorious for crowd-pleasing antics like tossing three balls in the air to serve, then hitting one. He once did it on match point and hit an ace. The record books show the Californian reached the final of the 1941 U.S. National Championships (now the US Open) and defeated Bobby Riggs in 29 of their 64 amateur and pro matches.

Despite his considerable gifts — most notably, a powerful classic backhand considered second only to that of 1930s superstar Don Budge — he was remembered “as the greatest player never to win anything” of importance. In 1941, Budge said, “When Kovacs forgets his horseplay … there’s nobody he can’t beat.” Frankie’s lame response: “When I get grim on the court, I dump the ball into the net or drive it over the fence. I can’t stand the strain of being tense. … I’ve got to have laughs to play good tennis.”

The Bucharest buffoon

Not since Kovacs had big-time tennis witnessed anything like the buffoonery of Ilie Nastase (left) in the 1970s. Although Nastase, a superb athlete with a dazzling array of shots, won the French, Italian, and US Opens plus three Slam doubles titles (two with Connors and one with Ion Tiriac), he surely would have achieved much more had he not been a compulsive jokester and provocateur. The incorrigible Romanian ‘mooned’ a referee, threw his shoe at a baseline judge who had called a foot fault on him, and changed his shorts during a match. Once he let a stubborn umpire know it was raining too hard to keep playing by standing under an umbrella (he borrowed from a fan) to receive serve.

Bud Collins, the esteemed journalist and broadcaster, nicknamed him ‘the Bucharest Buffoon,’ while others called him (just plain) ‘Nasty.’ During a London indoor tournament against Nastase, a ruggedly built Clark Graebner, who was furious at the Romanian’s baiting the crowd, officials, and him, hopped over the net, jabbed his opponent in the chest, and warned him not to try any more dirty tricks. His bluff called, a terrified Nastase walked off the court, saying “I’m too frightened to continue.” Nastase and a forgiving Graebner, who were friends and occasional doubles partners, went drinking afterward.

Other incidents ended less happily. In a mixed doubles match at Nice, Nasty whacked Frenchwoman Gail Chanfreau in the body with powerful volleys. Enraged, she threw her racquet at him. Nastase also nearly got into a fistfight with intensely competitive Cliff Richey during a Paris final, and Nicki Spear, a mild-mannered Yugoslav, tried to slug Nasty, who had cursed him and his female relatives in a Boston doubles match. Nasty’s obnoxious behavior in a Rome doubles final caused a near-riot that police had to be summoned to quell. And who can forget his infamous 1979 US Open match against McEnroe when fights broke out among dangerously inebriated spectators protesting Nasty’s disqualification for repeatedly arguing a point penalty.

What made Nastase tick? In 1976, the popular psychologist Dr. Joyce Brothers speculated about his aberrant behavior in Tennis magazine. “With children, temper tantrums are normal. When older people act up, it’s usually because they’re getting something out of it. Nastase likes attention and because tennis has been considered a gentleman’s game, he keeps his opponents so shook up they can’t concentrate.”

This decade, Nick Kyrgios, Benoit Paire, and Alexander Bublik crave attention so much and compete so little that they masochistically self-destruct with underhand serves and other foolish shots on big points. They haven’t figured out the balance between showmanship and smart shot selection.

The worst culprit

The worst culprit, though, is Gael Monfils, a 37-year-old Frenchman. Pundits have raved about his breathtaking athleticism since he won his nation’s Under-13 and Under-14 100-meter Sprint Championships and starred in the juniors.

Recently on social media, Monfils said, “People don’t let you believe in your own dreams. People don’t know you. This is why I try to have interactions with my real fans. I don’t need to win 20 tournaments, but if I win one match here, another match there, this is what it is about.”

That cavalier, low-expectations, uncompetitive attitude has often been what it’s about for Le Monf. When he lost the fifth set 6-0 to Andy Murray at the 2014 French Open, former world No. 1 Andy Roddick tweeted that Monfils put in a “horrible effort,” adding “showboats when winning and rolls over when down.”

After his 6-4, 7-5 loss to Poland’s Jerzy Janowicz at the 2015 Cincinnati Masters, Tracy Austin, a Tennis Channel analyst and two-time US Open champion renowned for her steely competitiveness, accused the well-liked Frenchman of not trying his best — the worst sin an athlete can commit. “To not give 100 percent and be so blatant about it, I think it’s disrespectful. It looked like an exhibition tennis. We’ve seen that way too many times with him. With Gael, it’s so difficult to watch because you know his upside ceiling could be so big, but he just goes away and doesn’t even try.”

Several years ago, during what should have been the prime of his career, Gael admitted he cared more about entertaining than winning. What a sad admission for any professional athlete. His job was to compete, compete tenaciously for every point. In a parallel way, his job was to train rigorously so he would not get exhausted in the middle of matches, which he sometimes did. His job during the past 20 years was to try to develop an all-court game, which he never did.

For all his acclaimed athleticism, 90 percent of it was limited to the baseline and counterpunching. His job was to try to hit the right tactical shot at the right time, especially on big points — not the flashy, low-percentage shot, which he, like Kyrgios and other would-be entertainers, often missed.

When you read the quote above by Gael, could his “dream” really have been to reach just one Grand Slam semifinal during his 20-year pro career or to rank in the top 10 only twice in the year-end rankings?

Considering his lean, muscular 6’4” physique, his marvelous natural ability, and his generally excellent technique, Gael should have achieved much, much more, while entertaining at the same time. Tournament tennis requires character and commitment, which all champions have in abundance. Lamentably, the sports world — and even Gael in his heart of hearts — knows he lacked both.

What role do social media and Tennis Channel and other sports networks play in creating, or, at least, perpetuating showboats like Monfils, Bublik, Kyrgios, and Paire by frequently replaying — and glorifying — their ‘shot of the match’ highlights?

After all, if they don’t gain immortality by winning Grand Slam titles and Olympic gold medals, at least they get the proverbial “15 minutes of fame.” Or maybe just 15 seconds on TV. Perhaps that’s all that some athletes today want, considering their short attention spans and a fear of losing if they do actually compete. Instead, they rationalise their abnormal behavior and losses.

Federer’s sublime brilliance

No champion fused ‘the art and the fight’ with the sublime brilliance of Roger Federer, and that undoubtedly accounted for much of his extraordinary popularity. The Swiss maestro won the ATP Fan Favorite Award a record 19 times, almost as many as his 20 Grand Slam singles titles, along with 13 ATP Sportsmanship Awards, another record.

But that fusion didn’t come early or easily. Much like enfant terrible Bjorn Borg and the rebellious Andre Agassi, Roger behaved badly as an immensely gifted but tempestuous teenager. “When I was 12 years old, I was just horrible,” he recalled about his frequent swearing and throwing his racquet. Working with a sports psychologist, Christian Marcolli, from age 18 to 20, completed his transformation into a calm competitor able to channel his exceptional athleticism and shot-making without stifling his creativity.

Much of Roger’s enduring appeal came from his uniquely elegant style. Ironically, his graceful one-handed backhand earned the most praise though it was often the weak link that Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic exploited when they dethroned him. However, all his strokes, along with his ethereal movement, enthralled players, coaches, and fans from all walks of life.

McEnroe, who once owned an art gallery in New York City, commented, “Roger Federer is the most beautiful player I’ve ever seen on a tennis court, without question.” Kathryn Bennetts, who runs the Royal Ballet of Flanders in Belgium, likened the graceful, coordinated, and skillful movement of Federer to Mikhail Baryshnikov.

“He has this smoothness to him,” Bennetts told the New York Times. “An ease that makes him special. He’s an artist, so refined. Like how dance transports you to a different place, so does he.”

The most oft-quoted encomium of Roger came from the renowned writer David Foster Wallace, a tennis lover. Wallace invoked religion to praise the beauty of Federer in his 2006 New York Times essay “Federer as Religious Experience”:

“The metaphysical explanation is that Roger Federer is one of those rare, preternatural athletes who appear to be exempt, at least in part, from certain physical laws,” rhapsodised Foster. “Good analogs here include Michael Jordan, who could not only jump inhumanly high but actually hang there a beat or two longer than gravity allows, and Muhammad Ali, who really could “float” across the canvas and land two or three jabs in the clock-time required for one.

Federer is of this type — a type that one could call genius, or mutant, or avatar. He is never hurried or off-balance. The approaching ball hangs, for him, a split-second longer than it ought to.”

Federer relished showing off his bold, jaw-dropping shots in big matches. In the 2005 Australian Open semifinals, he held match point against the redoubtable Marat Safin. When he sprinted beyond the baseline to reach a superb lob, the Russian smartly raced to the net. Instead of lofting a high lob to hang in the point, Federer foolishly attempted a 100-1, between-the-legs, back-to-the-net trick shot. It missed badly. Safin rebounded to upset Federer, and in the final, easily defeated Lleyton Hewitt, whom Federer would have been heavily favored to beat.

The Great Ones have short memories, though.

In the 2009 US Open semifinals, Roger conjured up another audacious ‘tweener’ on the penultimate point of his 7-6, 7-5, 7-5 victory over rising star Novak Djokovic. When it whizzed by the stunned Serb, the crowd erupted in thunderous cheers.

The Great Entertainer called it “the greatest shot of my career.”